Dear fellow travellers,

Christopher Nolan is no stranger to imagining disaster. His Dark Knight trilogy, adapted from various Batman comic-book stories, toys with various visions of urban destruction, both physical—those involving guns and explosions—and psychological, with each of the films’ major villains threatening no less than full-scale urban breakdowns. The cycle even concludes with the detonation of a nuclear bomb: here, symbolically the ultimate threat and one that even, shock horror, appears to kill our hero. Following these, the director’s sci-fi epic Interstellar explored the aftermath of what would, in the real world, mean effective apocalypse—irreversible climate change; global crop scarcity—but in this tale is heroically mitigated with an interplanetary expedition and, indeed, an actual, quantum alteration of history. Tenet, another film that fantasises the pliability of time, follows the attempt to avert another disastrous detonation, this time of a weapon that could destroy not just a single metropolitan area but the whole world. (“Including my son,” intones Elizabeth Debicki, insightfully.)

Such imaginings, of course, are ten-a-penny in Hollywood and have been for decades. Susan Sontag, in her influential 1965 essay ‘The Imagination of Disaster’, aptly summarised the links between the looming nuclear threat and the then-recent cycle of speculative science-fiction films; her observations have remained relevant through the subsequent years and countless cultural trends. Much of Nolan’s work certainly sits within this space of allegory and speculation. With Oppenheimer, however, he pushes further and does something fascinating: he swings his lens right to the source of modern pop cinema’s apocalyptic fixation. His film, in so doing, explores and to an extent explains this very fixation.

As discussed on the podcast, many of Oppenheimer’s roots are in the Hollywood of the 1950s—a milieu, incidentally, that’s ambient in the film’s red-scare subplot. This is a large-format, star-studded historical epic released into the midst of a global downturn in popular cinema-going, itself partly fomented on the one hand by sweeping structural changes within the film industry and, on the other, by a revolution in home-viewing options. So far, so Film History 101. But in its subject matter the movie also, unavoidably, refers to that aforementioned sci-fi cycle. In a sense, then, it uses its prestige trappings to outline the psychological conditions for the modern disaster imaginary, described by Sontag as

the trauma suffered by everyone in the middle of the 20th century when it became clear that, from now on to the end of human history, every person would spend his individual life under the threat not only of individual death, which is certain, but of something almost insupportable psychologically—collective incineration and extinction which would come at any time, virtually without warning.

This film is a biopic not just of J Robert Oppenheimer, the so-called “father of the atomic bomb”, but of the bomb itself: its design; its birth in the New Mexico desert; its role in the murder of thousands of Japanese citizens; and the profound long shadow it would soon start to cast on the psyche of the global body politic. Nolan, after Sontag, clearly argues that the atom bomb’s legacy is basically existential, serving an omnipresent ambient threat. Meanwhile, the film’s smartly jumbled narrative structure serves at least three purposes: one, it aptly represents a quantum-level interpretation of time and space; two, it evokes Oppenheimer’s guilt-ridden psychology as he works through his own memories of the Manhattan Project and its aftermath; and three, it reflects that broader state of existential panic that comes with contemplating this whole, sorry issue—that is, the “trauma” as outlined above. The terrifying hallucinations experienced throughout the film by our protagonist are often, pointedly, part of the general narrative flow engineered by editor Jennifer Lame; existing on the same experiential plane as both the film’s factual and subjective material. In this way, the movie formally maps the basic thought process of, surely, any viewer afeared of global annihilation. It’s something like a prestige history picture crafted as an extended nightmare.

Oppenheimer, then, seeks to explain something inherent to various strains of visual art and popular culture these last several decades. It also, clearly, seeks to explain Christopher Nolan’s cinema more specifically. As outlined above, Nolan’s films (at least post The Dark Knight, the billion-dollar hit that initially brought him industrial carte blanche and pop-auteur purchase) are marked by their working-through of disaster, violent threats to loved ones and outright Armageddon, and with Oppenheimer he steers his usual obsession with clever-clever chronology towards something quite direct and personal.

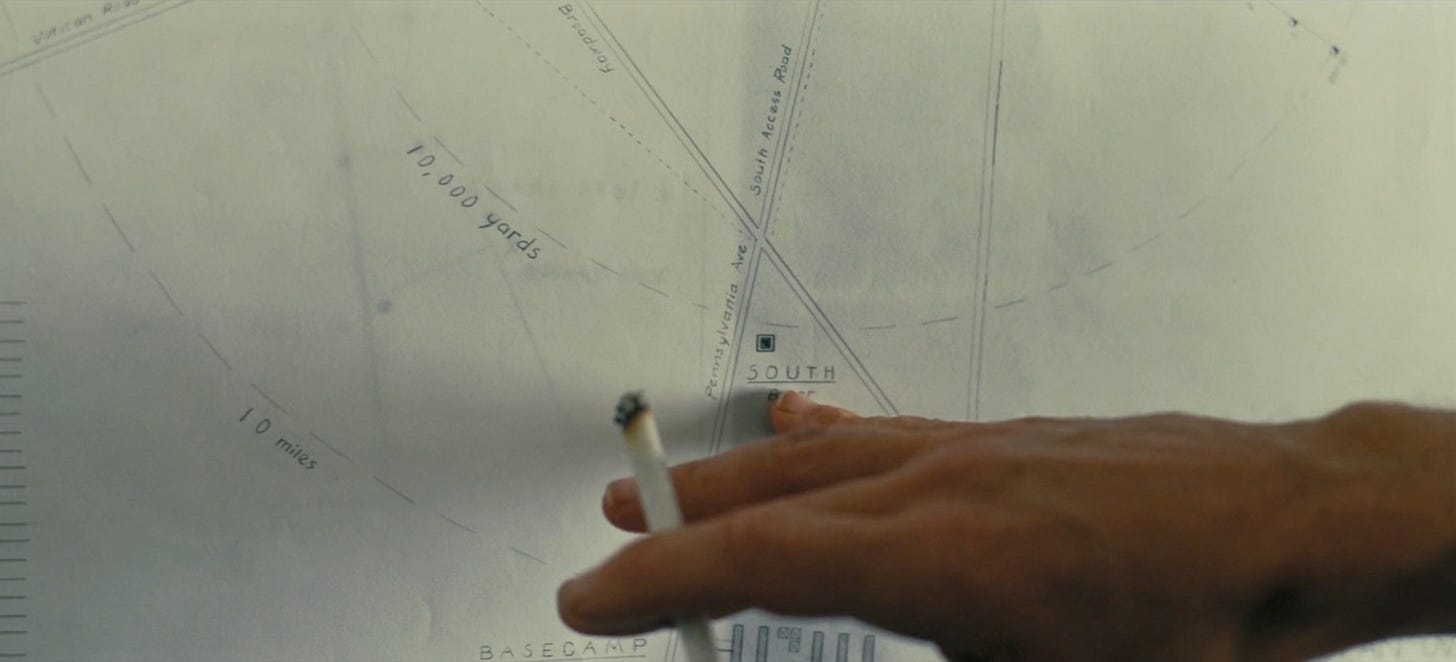

Through this, could the film serve, secondarily, as an allegory for large-scale filmmaking? Of course. Just look at Oppenheimer’s meticulous visualisations of the Los Alamos team’s process; those small details, right down to things like white labelling-tape and blast-radius calculations, that Nolan focuses on as he follows the gestation and explosive birth/death of the first test bomb, bespeak an interest in, if not obsession with, the mundane work that builds such a monumental end product. This is, for its first two hours, essentially a movie about project management. But after the first test explosion, Oppenheimer’s underlying linear structure pushes instead into a drama that explores guilt, culpability and the bureaucratic banality of evil: the moral rot that attends project-managing the end of the world.

At this point, we can return to Sontag. Her notes on the imagination of disaster conclude rather more complexly, as she thinks through the ways that genre movies have simultaneously spoken to her generation’s Cold War fears and neutralised them, confining them to the realm of fantastical fiction. She allows that this “is no more, perhaps, than the way all art draws its audience into a circle of complicity with the thing represented.” But the films nevertheless “inculcate a strange apathy concerning the processes of radiation, contamination and destruction” or, in other words, an “inadequate response” to the nightmare of reality.

One can therefore spiral further through Oppenheimer’s various layers: to what extent is Nolan, who wrote much of his screenplay in the first person and at one point casts his own daughter as the hallucinated victim of an atomic blast, aligning himself not only with his protagonist’s genius for project management (I know: riveting) and his anxiety over a nuclear reality, but also with his deep guilt over his own product? Is the film as much a rejoinder to Nolan’s own prior imaginations of disaster as it is an explanation for them? (As an extreme, and far less abstract, example of this: one wonders how often he reflects on the unfortunate and doubtless unsettling fact that a screening of the third entry in his techno-militant Batman vigilante series was the setting chosen by a schizoid loner to carry out a gun massacre.)

It is this underlying uncertainty toward its own existence, its own need to be, that aligns Oppenheimer with what is perhaps its most peculiar context: the 100-minute Mattel company stock-jacker that comprises the other half of the global “Barbenheimer” phenomenon. Greta Gerwig’s effervescent comic fantasy, released to cinemas on the same day as Nolan’s nervy, middlebrow epic, takes its titular doll out of the plastic, fantastic Barbieland and into the world of humans, where she undergoes education in biology, patriarchal oppression and—far more awkwardly—the cultural legacy of the Barbie brand. If Oppenheimer is a spectacular, whorled biopic of the atomic bomb and the origins of an entire global mindset, so too is Barbie a loose biopic of a product and its influence on the popular psyche. Of course, where Nolan’s film is pretty clear in wishing its central product had never been made, Gerwig’s mission is marked by an ambiguous and perhaps inherently doomed blend of critical comment, corporate compromise and deep personal connection between filmmaker and subject. Barbie succeeds when it articulates the role of the doll in Gerwig’s own childhood, and the emotional importance of toy to human; more often, though, its screenplay is a confused apologia, constantly mounting the beginnings of necessary critique before shortly neutering itself, its ingenious satire on unearned masculine dominance quickly ceding to a far less-than-radical statement of corporate, self-serving, ultimately very Hollywood quasi-feminism.

The point of this brief comparison is simple: to highlight the way that Oppenheimer, as with its unlikely blockbusting sibling, reflects through its fractured, personal presentation of an unsettling totem of recent history the ethical confusion forced upon all of us in a post-nuclear, post-plastic, decidedly terminal-capitalist globalised world. Like Gerwig, Nolan bakes both a fascination, scepticism and even disgust with his subject into his film and finds a way to articulate the fact of its cultural centrality. (And in a vague sense, the outsize financial success of both releases rather prove that centrality.) As that perfect adolescent complaint goes, none of us asked to be born; and Nolan captures, within and without his film, something of the compromise that attends simply existing in the years since that severe atomic irruption and the American empire’s plasticky postwar industrial growth-spurt: the evils one may be complicit in while going out of our way to do good in other areas.

Rather uncomfortably, it’s possible that the real summation of all this came with the director’s acceptance speech at the Academy Awards, where Oppenheimer triumphed: despite his film’s attention to the USA’s bloodthirsty willingness to use the logic of defence in the execution of thousands, and the way its military-political apparatus will do what it can to smear any who so much as express light misgivings about this, Christopher Nolan became strangely unwilling to mention the country’s, or indeed his own country’s, direct and crucial involvement in the overseas destruction of Gaza and the genocide of its people, at that moment gravely current. Such a mention would, to be sure, have been a token gesture. But a strange omission, nonetheless, given the context of the evening and the content of the film. Could it be the case that Nolan’s serious-minded treatise on the nuclear anxiety in popcorn movies is, in fact, merely another participant in the “fantasy” playground that Sontag identifies? Perhaps, for this director, wallowing in the disaster imaginary really is enough.

As ever, thanks for listening to the pod and please do share us around with your pals, your loved ones and your fellow scientists.

—Calum & Eddie

Share this post